Pay Inequities Between First- and Third-World Nations: Distributive Justice

Rawls and Distributive Justice

Maiese has noted that distributive justice is concerned with the fair allocation of resources among diverse members of a community. Fair allocation typically takes into account the total amount of goods to be distributed, the distributing procedure, and the patterns of distribution that result. From a Rawlsian analysis I will show the limits of distributive justice in terms of utilitarian objections, and a response by Hugh Lehman. Rawls argues that resource allocation should be based on the ‘difference principle’ which is a system that measures overall utility based directly on the consequences of those who are effected the most negatively. “The difference principle is a relatively precise conception, since it ranks all combinations of objectives according to how well they promote the prospects of the least favoured.” (Rawls, 280)

“Justice is happiness according to virtue. While it is recognized that this idea can never be fully carried out, it is the appropriate conception of distributive justice, at least as a prima facie principle, and society should try to realize it as circumstances permit.” (273) But to whose circumstances has always been an important question. By crossing cultural boundaries we are invariably drawn to make either realist or liberal assumptions about how to approach international discrepancies, which we would not have to make if we were not applying it across cultures. These assumptions will tend to colour ones view on distributive justice.

Regardless, there is an argument that the equal moral worth of all humans need not be considered as justification for equal distribution of resources. “The essential point is that the concept of moral worth does not provide a first principle of distributive justice…thus, the concept of moral worth is secondary to those of right and justice, and it plays no role in the substantive definition of distributive shares.” (275) From this we are given Rawls’ position, namely, that inequality within distributive justice is the norm and that organizations have no functional commitment nor obligation to recognize equality.

As mentioned, this issue takes on another dimension when we are observing pay inequalities between first- and third-world nations because we are dealing within an international-relations framework. Instead of trying to make distributive justice fit within the international context, Rawls claims that the sui generis nature of assistance is just a by-product of the international case, much like egalitarian reforms would result from the domestic case.

Distributive justice is a measure observed in Canada under the federal equalization program; it is also controversial. Many have pointed to what is referred to as the ‘equalization-trap’ in which regional inequalities are not addressed whatsoever. Instead, provinces are presented with an unconditional cash transfer that pays next month’s rent. The issue becomes; what incentive do provinces have to better their means when it could mean that by doing so, they forfeit their rights to what is, in effect, free money.

Further, when we look at case of international subsidies, we see some of the limits of distributive justice, and Rawls agrees that if an obligation to DJ results in injury to the wealthier actor, then divestment should be encouraged. This is simply because it is of little good to the rest of the system. However, more and more we are seeing domestic policies inadvertently spill-over into foreign affairs, which means powerful hegemonic influences can perpetuate inequalities in the guise of national interest. Case in point would be European agricultural subsidies that put undue pressures on North American markets, especially Canadian ones.

Therefore, in the international context, Rawls would claim that there is no obligation to distributive justice, not because it would be too complex or difficult, but because it would be impossible for any one actor to possess moral authority above and beyond other, just-as-moral actors burdened by their own sovereignty issues.

Beyond Rawls

Henry Shue has suggested that there are three main variations of the ‘equal pay for equal work’ principle. For example, does equal pay mean that workers in third-world nations should receive equal dollar-for-dollar compensation? Or does it mean that they should be entitled to carve out the same standard of living as a worker in a comparable job in an industrialized country? Or maybe they should be entitled to the same standard of living as a worker in a comparable job under comparable economic status? “Shue concludes that the equal pay for equal work principle ought not to be understood as applying regardless of social context.” (Lehman, 445)

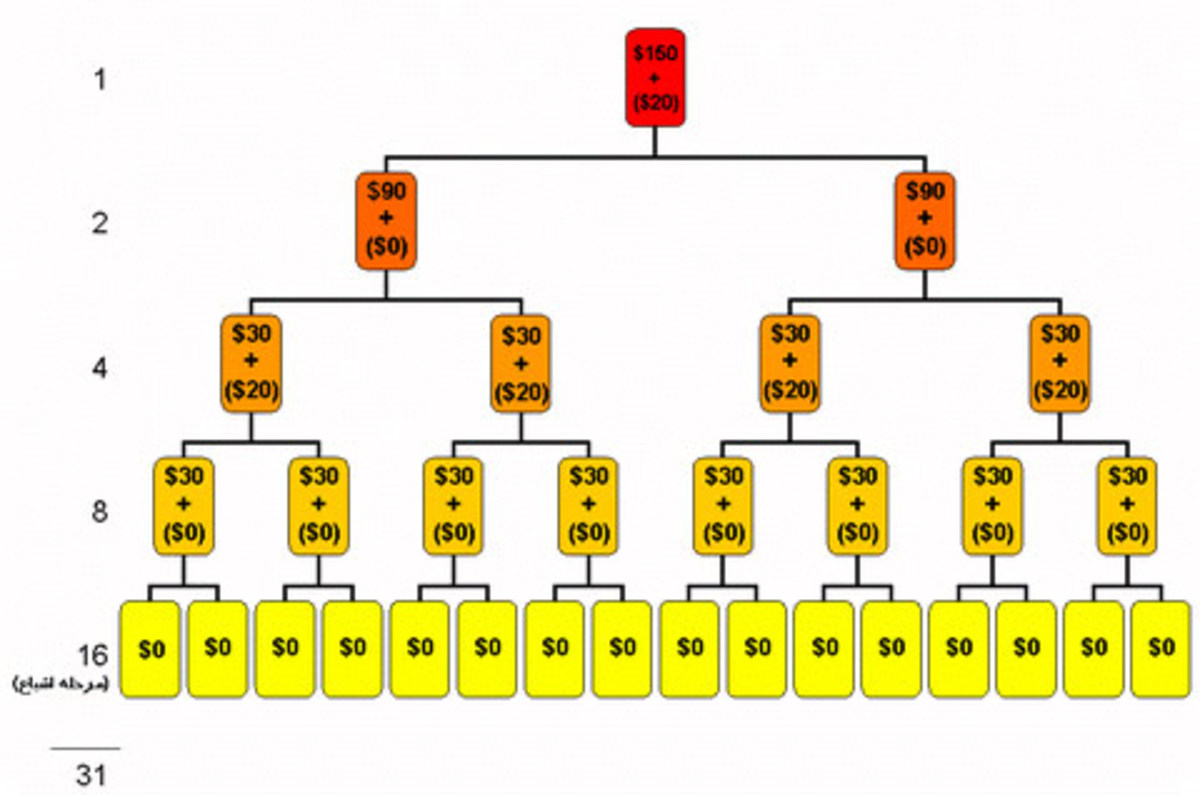

“On utilitarian grounds, corporations should be encouraged to transfer operations to third-world nations subject to the condition indicated, namely, that there be significant improvements to the quality of life of the poorest people of those nations.” (446) This is an argument claiming that by moving these corporations to poor nations, there is a maximization of utility.

However the Lehman article points out that the overall maximization of utility, on its own, has little relevance especially against the equal pay/gender argument in developed countries. “The policy of permitting lower wage scales for workers in Bangladesh and comparable places need not be unjust. We have argued that it is in accord with the difference principle. It is also in accord with the principle of equal consideration of interests.” (447-8)

So while we can use the utilitarian argument to a degree in the international context, it is of little use to defend against, say, wage inequalities between men and women in Canada.

Lehman also the raises the question as to what constitutes the maximization of utility when it comes to improving standards of living. In matters of starvation, a loaf of bread does far more than a paper bill. The point is that if we are comparing different cultures we should obviously not assume that equal dollar-per-hour pay translates into the equivalent increase in standard of living. “Thus, rather than requiring corporations to provide equal pay for equal work, one would choose to require corporations to make significant improvements to the native water supply, sewage, hospitals, etc. Such improvements would improve quality of life far more than the greater salaries required by the equal pay for equal work principle.” (446) It is this type of argument that will stall the utilitarian.

“It may be that a worker who has had a job has a right to that job. He ought not to be replaced by another worker if he is doing the job well. However, for new jobs, it is not at all clear that workers in one country have a right to those jobs.” (448) Here, Lehman touches on the concept of corporate welfare, the merits of which are hotly contested today. The potential failure of Detroit’s Big 3 auto-makers has brought this contention into households everywhere. To what extent do people have a right to their jobs? This question is intended to highlight the importance of the cultural context in which jobs exist. It is a chicken-and-egg comparison depending on one’s market-orientation. Do jobs draw people in and create a marketplace or are jobs simply a by-product of human concentration of interests. Obviously, in a mixed economy a balance must be struck between preserving people’s job security and competing economically. The crux, however, of the ‘unequal pay for equal work’ argument is the underlying notion that creating these jobs in the first place, has an advantageous effect on local standards of living.

Lehman ultimately rejects the equal-pay-for-equal work argument. “Were it reasonable to believe that a foreign corporation could contribute toward the reduction or elimination of injustice in South Africa while paying black or coloured workers in that country less than workers in industrialized countries are paid for doing the same job then I believe such investment should be encouraged” (448) I tend to agree along the lines that distributive justice has reasonably shown that corporations should have no obligation to the equal-pay-for-equal-work argument because it is not an accurate indication of how distributive justice should apply across borders.

References

Heath, Jospeh. Rawls on Global Distributive Justice: A Defence. University of Toronto Department of Philosophy. <http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~jheath/rawls.pdf>

Lehman, Hugh. “Equal Pay for Equal Work in the Third World”. Journal of Business Ethics. 1985. pp. 487-491

Maiese, Michelle. "Distributive Justice." Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Research Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: June 2003 <http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/distributive_justice/>.

Rawls, John. A Theory Of Justice. 2nd Edition Revised, OxfordUniversity Press. 1999